How to structure a big project in Cypress

Cypress will give you a project structure out of the box, but as the project grows, there are different files introduced into it that need their place. Also, there’s an ever-lasting debate on whether use page-objects, and if not, what should be the alternative. In this blogpost I would like to share my view on how a successful project should be created and structured. This is based on my almost 7 years of experience building different projects with Cypress.

Fundamentals and principles

First of all, let’s talk about some of the principles on which my thoughts are based on. These formed my decisions in my previous projects and that were vital to making the project successful. In other words, not everything mentioned here may apply to every project. It is kind of given, but I still want to mention this. Mostly to avoid "this would not work for us" responses. So here they are:

QA automation should be a part of source code repository. I recently made a poll on LinkedIn and found out that 45% of responders do not have their test suite in the same repo. In my opinion test automation code, (and especially when using Cypress), should not be detached from source code of the tested application. This keeps all tests and all branches in sync with development, makes it easier to do continuous delivery. This also means that developers are invested in creating and maintaining test automation as well as testers.

Readability is (the most) important decision maker. Having a failed test might not be enough to identify what went wrong. Testers are information providers. This means that if a failed test does not provide enough information on what happened or why it happened, that tester did not do a good job. When writing a test, readability of the test should drive every test design decision.

Testing should improve speed of delivery. Our users don’t care about how fancy our tests are, but what value does the product bring to them. For a successful company it is important to bring that value and to bring it fast. What this means for testing? It should start early and test automation has to be as fast as possible. Slow debugging and slow testing means slow delivery, that’s why test automation should be optimized for speed.

Human time is more expensive than machine time. Saving costs on CI is generally a good thing and writing test automation can speed things up. But there’s a limit to how much time you want to spend on it. It is important to choose your battles and make sure that creating a test automation will actually save you time. Everything you build will need maintenance, and it’s important to think about that, especially when deciding between building a tool vs. paying for a solution.

If you find yourself disagreeing with these principles, it’s OK. This does not mean that I think you are making bad decisions with your tests. I’m sure you are doing good, but maybe working with a different context. As a result, this forms different principles and drives different decisions. This will always be a reality in tech, especially given how diverse are applications of tech.

IMPORTANT NOTE: Having said all this, I’m not 100% set on everything. As time goes by and I gain more experience, I adjust my views and apply different principles. Feel free to discuss this with me on Discord, I will be happy to learn about your insights to this.

BDD without Cucumber

Tests I write often reflect a certain behavior or describe how a certain feature is used. When I started creating test automation, we had 15 most important scenarios written down with my colleague and we would race each other into who completes them faster (she - manually, or me running test automation).

This has basically made our test automation behavior driven, although we have never decided to go with Gherkin syntax or the Cucumber framework. The simplicity of Cypress commands was good enough solution for us and made it quite apparent what the test is doing. Early enough, I have found this tweet by Kent C. Dodds that we decided to live by:

This meant we wanted our tests to follow a certain scenario and then grouped scenarios into features. A result of such test structure looked something like this:

Folders represent a certain feature and spec files inside those folders would represent a behavior or a user story that this scenario would cover. As mentioned, these scenarios represent real user behavior, but are not written in Gherkin syntax (Given, When, Then) or using Cucumber framework. Although open source community around Cypress has created a Cucumber preprocessor that allows you to write your test like this, I generally lean away from this solution.

In my opinion it adds an unnecessary layer inbetween test code and the application. This slows down test creation and adds unnecessary maintenance. Before you can write a complete test, every step definition needs to be created first. Every new step needs at least one new step definition unless we are creating just a different combination of existing steps. But in that case, there’s no real value in adding such test to existing test suite as all steps have already been covered.

That being said, BDD approach has brought a focus on user behavior, which I definitely agree with. In my opinion, Cypress commands are already behavior focused, as most of the commands read like a sentence:

Arrange, Act, Assert

Rather than going with "Given-When-Then" approach, I like to go with Arrange-Act-Assert. They are very similar in their fundamentals, but I feel like the latter approach defines the testing goal more clearly. "When" keyword in the Gherkin-style syntax seems a little bit ambiguous as it is not always clear if it refers to an action or to a state. The "Arrange-Act-Assert" pattern makes it clearly.

Usually, the "Arrange" part happens via API calls, or database setup and rarely via UI. More often than not, this step takes place in before() or beforeEach() hook.

When it is hard to decide whether a part of test should be done via UI or API, the Arrange-Act-Assert pattern helps on deciding. Everything that is done via UI is part of "Act" step. Everything before that goes into "Arrange" part and is not done via UI.

"Act" and "Assert" steps can happen multiple times during end-to-end test.

Test annotation

As mentioned at the beginning, readability is really important. This helps navigation through tests simple. While it may seem like a small detail, it is actually really valuable when you need to debug a test. When writing an it() block, the name of the test should give you enough information about what is the test scenario. Some good and bad examples:

Ideally you should write your test title in such a way that you can imagine what the test is doing without looking into its content. Once my colleague recommended that the it and the name of the test should read like a sentence. I really like this approach although I have found cases where that was counterproductive and would push me into weird test namings.

Don’t overcomplicate stuff and if a rule needs to be broken, break it.

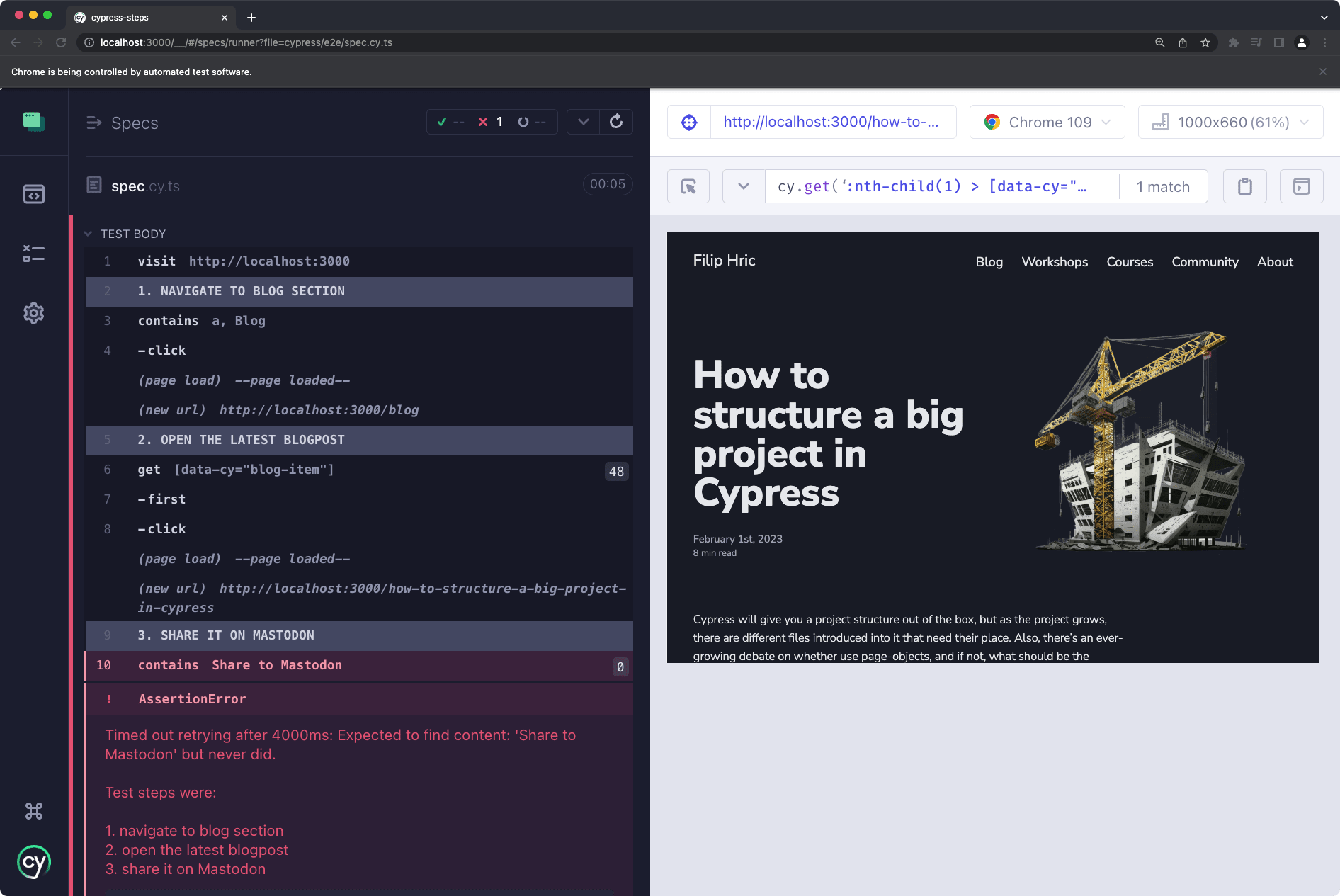

Another useful way of making tests more readable is to add your own custom logs. Gleb Bahmutov has a useful plugin for logging into terminal, which can be definitely help with test annotation. I personally like to add steps into my tests to annotate the test scenario. I have created a plugin which does the following:

- every

cy.step()command describes a step in a test - every

cy.step()command is automatically numbered - whenever a test fails a numbered list is appended to the error message

- the error message is printed to the terminal and the failure screenshot

Spec files

Every spec file should contain just a handful of tests. End to end tests tend to be longer, which means dealing with more lines of code. Once you have multiple longer scenarios in your spec file, it may quickly become harder to navigate through.

I also rarely decide to use describe() blocks, as the real value of these blocks comes in when you have at least two in a single spec file. describe() blocks help group together tests that have something in common. Most of the time it’s before()or beforeEach() hooks. This is why in cases when I need to split the groups, I usually split them with a new spec instead of new describe() block.

However, there is a problem with this approach when you try to use "Run all specs" button in Cypress open mode. This mode basically creates a single spec out of multiple files, which means that all your before() and beforeEach() hooks get concatenated causing unexpected results. This is something to be aware of. When working on a big project however, I practically never run all specs through open mode.

Selectors

I have tried different approaches in the past, but I ended up going with Cypress’ recommendation and add data-cy selectors into the application. This has proven to be the most stable approach. Relying on class names has always led to random failures. This was especially true these days as developers rely on UI libraries such as material design or bootstrap. Updating these can often cause a change in classes, which breaks our tests.

Knowing what to select

Adding your own data attributes for selectors can help you learn more about the application you are testing. Let me demonstrate this by a simple example. Imagine that you have a button that looks like this:

In your test you want to click in this element. Notice that the button has the disabled property, which means a real user would not be able to click on it. This means that targetting the correct element becomes super important:

This is why choosing the right selector is important. When adding your own data-* attribute can help you understand where does the interaction in your application happen.

I would also advise to add your data-* attributes yourself even if you are a tester or not the person developing the app. You will get a better understanding of the structure of the app and also get yourself familiar with different frameworks. Also, I don’t find it particulary useful when the addition of data-* selector is outsourced to developers. This prolongs the feedback loop and adds unnecessary overhead.

Removing duplicity, improving readability

Another advantage of adding your own selector attributes to the source code is that it removes the duplicity that is created when using page objects. Same goes for storing your elements in a separate file. It is another concern to be taken care of and a de-sync between the reality of the application and tests can happen easily.

Adding data-* selectors can also help you improve readability of your tests, as you can add anything that makes sense for the test you want to write. Some people I talk to are concerned about a naming convention, but I would not worry about it. Having two of the same data-* attributes is not a problem until they are found within the same test or within the same screen. I’d definitely advice for using selectors that represent what user sees, instead of trying to come up with a naming convention that would embrace every selector in tested app.

Selector strategies that make sense

A valid concern for using data-* attributes is a situation when this attribute gets changed or deleted. In my experience, this happens less often with this approach. This is mostly because these attributes never get changed or deleted by accident, due to a framework update or some other unrelated change. If an attribute gets deleted, it usually happens with the element as well. And in that case your test actually should fail. In case of an attribute renaming, a simple "find and replace" action does the job.

Another question that I see raised more often is the usage of Cypress testing library. Personally I haven’t been using it a lot, but I see the value in using it. This library often pushes you to rely on accessibility attributes, which means you test two things at once. Not only you check functionality of your app, but you make sure that it’s accessible as well.

Most importantly, you can use multiple selector strategies that complement one another. This amazing blogpost by Mark Noonan demonstrates how different levels of testing strategies can work together to create a very stable test suite.

I have experimented with mapping all of the selectors and making them autocomplete, but this strategy does in fact rely on a single type definition file which stores all selectors. In theory I can imagine that this might work, but but currently I’m more leaning to this strategy being a dead end. But you be the judge.

Custom commands

Custom commands are one of the most powerful features of Cypress. The fact that you can expand your library makes Cypress ecosystem exceptionaly versatile. I usually use three categories of custom commands:

- utility commands

- API calls

- action sequences

Custom API actions

With Cypress, you will often times find yourself calling an API to either set up your data or to do some action in your app. Since you may not always want to call cy.request() and provide needed authorization, headers or request body, creating custom command seems like a good idea. You can create a function that will take care of default values, or you can pass different arguments to alter the behavior. Data used from API call can be later used in test or can be processed within the test.

Utility commands

If you use data-* selectors, creating a cy.getByDataCy() command might be useful. Utility commands usually take care of some niche case within an application. Some examples include cy.getClipboard(), cy.getTooltip() and so on.

Action sequences

Action sequences resemble the traditional page object model the most. These are series of UI steps that cannot really be avoided by calling an API. Most of the time they deal with situations that take multiple steps and are essential for the test flow. An example might looks something like this:

Organizing custom commands

My rule of thumb is to put every custom command into it’s own file and add them to their own folder in the Cypress project:

The commands folder can contain categories of custom commands, but I am not strict on following this rule. Since custom commands usually have their own unique name there’s not really a big benefit for creating subfolder.

Every command is in its own file and contains the command as well as the TypeScript definition. An example of such command looks like this:

Cypress documentation recommends creating a central index.d.ts file which contains type definitions for all commands. I personally lean more to the approached shown above, as this way the type definition is contained in the same file as the command itself. This creates less confusions and it’s much easier to maintain.

Every command has its own JSDoc comment that provides additional information into what the command does. This is incredibly useful for anyone new who joins the team. It also keeps the code self-documented and can point to useful links e.g. to internal wiki.

Instead of using Cypress.Commands API, each command is written as a function, and then imported into cypress/support/e2e.ts file.

Another approach that I tend to use is to have an index.ts file that adds all the imports from cypress/commands folder and import that to cypress/support/e2e.ts instead. This is useful if you decide to move your app into monorepo and add your custom commands into separate library so that it can be reused across your projects.

TypeScript

All my projects use TypeScript. The implementation of TypeScript into an existing JS project is super easy as it can be done gradually. TypeScript errors don’t actually affect your tests, but can help you find errors. TypeScript guides you while you are writing tests by providing autocompletion, checking of the parameters that you pass into your commands and much more.

TypeScript also works really well with Custom Commands. One way of how you can use TypeScript in your custom commands is to reuse types from your source code in your tests:

The code example above shows cy.request() command that will return types from Board interface imported from source code. This means that if you have an interface like this:

You will be able to spot a TypeScript error if you decide to write a test for something that is not part of the Board interface.

In addition to checking your code in your editor, you can set up a lint check that will make sure you don’t have any TypeScript errors in your codebase:

Running npm run lint command will ensure that any TypeScript error introduced by latest changes will be caught early. You can make this lint step run as a pre-commit hook and even prevent commiting such code. This check will take just a couple of seconds.

The biggest advantage though, is that it creates a two-way sync between source code and your tests. Not only it will make sure that your tests are typed correctly, but whenever a change is introduced on the source code side that changes types, it will affect the tests.

A nice bonus in the TypeScript world is the ability to define paths. This remove the headache of resolving relative paths in your project. Let’s say you have a path defined in your tsconfig.json

You can import a fixture file in your test like this:

Code coverage

I’ve explained how code coverage works in the past. It is a really powerful tool. While you may find some teams that aim for 100% code coverage, I don’t find this particularly useful. Code coverage report can serve as a map of of the applications "landscape" and can navigate you to unexplored areas.

Usually business cases are covered first, but there are many edge cases which often get forgotten and can cause our users’ disappointment. Code coverage helps finding those areas.

Code coverage requires an instrumented version of the app, which requires a separate build. This can often be solved by creating a custom step in the pipeline and I find worfkflow dispatch pipeline to be an ideal use case for that.

The coverage reports can be saved as artifacts, or you can use a service like Codecov that provides really beautiful insights into your code coverage. If you want to take a look at a living example of such report, you can take a look at my example repository with the Trello-clone app that I made.

Utilities

Every project is specific and comes with a bunch of common-pattern problems that need to be solved. To avoid solving the same problem multiple times, I put all my utilities into cypress/utils folder. This can by stuff like generateRandomUser(), getAuthorization() or some others. I usually import this right into my test instead of including them in support file. There’s usually not too many of these as Cypress comes with lodash library bundled in which is full of useful utilities.

Global hooks

There are couple of global hooks usually set up in my projects. The usual use case is taking care of cookie consent message. Adding an global beforeEach() hook can set up all the important cookies and prevent the message from opening in your tests.

You can always use cy.clearCookies() command to remove cookies in the test that tests this consent message.

Tagging tests

As soon as the project grows, it is pretty much impossible to run all tests on every commit. Splitting test into categories can be easily achievedy by using @cypress/grep plugin. It enables you to run a subset of tests based on the test name or based on tags.

First and foremost, @smoke category is created that takes care of the most essential scenarios. The smoke set can sometimes be a separate folder, but I personally prefer for the tests to live in their own feature folders.

A single test can have multiple tags, so that test can be ran based on a certain testing goal. E.g. @email tag to run all tests that use email validations, @mobile for all mobile tests, or @visual for all tests containing visual validations. I like to think about different situations in which we want to target a certain area of the application. For example, if CSS has changed, we might want to run all @visual tests, or if our email testing service is not working currently, we may want to temoporarily omit @email test subset.

In CLI, these can be ran by following command:

Configuration switching

It is important that test work on multiple different environments. To make things easy, I usually create a config folder that contains .json files with all the environment-specific variables such as baseUrl, url of the API, or some other information that may be used during the test. These get fed into env object from the .json file and can easily be accessed by Cypress.env()

The following setup will take care of adding the correct information to the project:

When running a test with a different configuration, all that’s needed is to run a test like this:

and Cypress will load all the variables needed.

Besides having the configuration set up in separate .json, there is information that should not be commited to the repositories, like passwords, api keys, etc. These are usually part of environment and are passed through CLI.

To make things easier, I use dotenv package that takes care of management of env variables by using .env file.

⚠️ Always make sure that

.envfile is added to.gitignoreotherwise you risk commiting sensitive information out in the public

To load the keys, dotenv package needs to be imported in cypress.config.ts so that env variables are loaded into Cypress and can be used during test.

Node scripts

The cypress.config.ts file can get bloated pretty fast, especially when setting up tasks or resolving configurations. This is why I started splitting these into their own files and add them to scripts folder.

This keeps the main config file clean and easy to read. It also makes it easier to maintain multiple cy.task() commands.

Documentation

Everytime a new member joins a team, they can either slow down the team, or make it more effective. That’s why having a good documentation is essential to successful onboarding.

Usually the documentation contains 3 important parts:

- installation of the projects

- explanations, recommendations, examples

- pull request rules (these can be added to the platform you use)

Installation needs to have all the information one needs in order to install and run project. This will be a living document, since changes introduced to the repository need to be reflected, but also because first version of the document is never sufficient enough. When an important information is missing, it may be useful for the newcomer to add that information to the docs and create their first commit.

Since every project has its own specifics, it is important to have these explained. What are the conventions in the project? How do you solve common problems. What are the conventions used in this repository? All these questions should be answered in the docs. The main goal of this document is to make your life easier, so ideally it should be easy to read, and if needed, split into multiple files.

I also find it useful to set some ground rules for pull requests. On many platforms, you can set rules on how many people should approve a pull request, add checklists and other requirements. While these may seem like too much, they are a great help that prevents you from forgetting something important when merging new code.

Final thoughts

Big projects are rarely about just Cypress commands and they have much more to do with the test design and project design. While having some thoughts on what is the best way, most of my projects are living organisms that change and evolve as time progresses and needs shift. My current structure looks similar to something like this:

I hope you were able to get some inspiration from this. I share tips like this more often so consider subscribing to the newsletter, and following me on Twitter, LinkedIn and YouTube.